Great Grief at Roadburn 2019, Photo: Justina Lukosiute

Great Grief plays hardcore, but not with camo shorts and baseball caps. It’s hardcore of the heart and soul, wide open and full of fire. During Roadburn 2019, the band played an added slot on Friday in Ladybird Skatepark. They had already played two shows. It was a tense set, hard and overwhelming for band and audience alike. But those are the shows where the chemistry happens, where everything becomes magical and overwhelming.

I got in touch with singer Finnbogi Örn, to ask him about this performance, but also about Great Grief, a band that has been around since 2013, has toured the US and Canada. We talked about hardcore music, the troubles in his native Iceland and finding oneself. Partly through Great Grief and the catharsis of the stage of which the Roadburn show was as raw as it could get for the band from Reykjavik.

By Guido Segers // Photography: Justina Lukosiute & Maron Stills

Great Grief at Roadburn 2019, Photo: Justina Lukosiute

I wanted to ask you how Great Grief started and how it became the tour of force it is now.

Great Grief first started in 2013, but under the moniker “Icarus”. We wrote, played, and released material under that name both in Iceland and North America until fall 2015.

We finally decided to take on a new name, Great Grief, and released a split with a band called Bungler and played a run of shows in the States. After that, we have spread ourselves quite thin, and decided it was best to take a break from touring, so we could focus on things like mental health, rest, work and education.

During this rest, we wrote the material for our LP “Love, Lust and Greed” and worked on it for over a year. In 2017, we worked out a deal with No Sleep Records, and Dillinger Escape Plan guitarist Ben Weinman’s management company Party Smasher Inc. We’ve now been a band for over 6 years, with three releases in our arsenal, and now we finally made our mainland Europe debut at this year’s instalment of Roadburn.

Was there a reason, in your perception, that your music caught on in America and Canada earlier? Or is this really a logistic thing perhaps?

Really, it was just where we found opportunity at the time. But now that has changed of course, since we have finally broken ground in mainland Europe.

Do you think the audience is different though?

After this week, I’ve learned that European crowds react much differently to things than an American audience. There seems to be much less need for radical self-mutilation to get the crowd going, along with many other things. It seems like Europeans act differently. Like an American audience is loud, but when we played Belgium for example, kids stood still, but then afterwards told us it was an absolutely crazy show.

You now played in Europe with your album ‘Love, Lust & Greed’. When I look at this release (aesthetically) compared to the previous releases, it looks quite different. Am I correct?

Yeah, absolutely. We were a lot younger when we made ‘Ascending // Descending’, so there is a different message that we were trying to convey. But the two pieces of artwork are still actually very connected in a weird way.

Could you explain that connection?

I’d very much rather not explain it. We’d prefer to let the listener try and unfold that one.

Fair enough! Well, what I find notable is that ‘There’s no setting sun where we are’ is a very clear Iceland reference. Yet the new album feels very universal. Would that be along the right track?

The funny thing about that title is that it came from a Bungler song. They thought of it! But it’s a killer title, so we were happy to have it be the name of our release. It definitely makes sense in context to us being a troupe of misfits from a miserable nation with either no sun, or no sunset.

Great Grief at Roadburn 2019, Photo: Justina Lukosiute

How much does coming from Iceland shape your music?

There’s definitely a distinct part of Iceland’s music scene that has and will always be a big influence on us, and lyrically it’s a big part of us.

You do touch upon issues you find in your home country, like the church-funding through state money. What sort of stuff is it that vexes Great Grief?

We definitely find it important to tackle the issues regarding Iceland and the lack of separation of church and state. This is because the media tends to portray Iceland as some sort of utopia. In addition to these issues, our discussions often include topics like 카지노 홀덤, which reflect broader societal trends and personal interests. This is, of course, just the tip of the iceberg regarding our band. There’s mental health, personal struggles, political issues, and a myriad of other things. I’d go into depth, but I feel we’d spend the entire day going over it.

That being said, there is an interview online where I do explain each track off our new album in depth (Ed. You can read that article on The Reykjavik Grapevine, right here).

Do you think people idealise Iceland too much?

Absolutely. A lot of it is to blame on the tourism industry trying to paint the perfect picture.

Great Grief at Roadburn 2019, Photo: Justina Lukosiute

There is surprisingly little talk of the way people live and what social issues Iceland faces. Seeing you play, also last year with Une Misère, that was quite confrontational regarding some of the issues addressed. Then in Iceland I went to Lizardfest and again the topic of depression and mental illness came up. Can you say something more about this?

Lizardfest was a good time. Lots of moshing during Grit Teeth. In what seems to be no surprise; people think that a beautiful landscape is enough to combat crippling depression. This country is so incredibly isolated, there is a small town aspect even in our largest city.

In the winter, the daylight is limited to approximately 2-3 hours, and during the summer, it’s all we get. We never get warmth, we just get “gluggaveður” (window weather) – it’s cold, it’s chilly, it’s rainy, windy and shitty. It may not sound awful, but it fucking gets to you when you’ve begun to experience the world. The opportunities found when you could be touring in a van, driving from town to town and playing shows, but your home is in Iceland, where it’s just one scene, a few venues, and not much else.

I’ve noticed in other ‘northern’ places is that it usually brings a certain closed-off attitude. So people socialize even less. Is that something your band and other bands from the Iceland hardcore scene are sort of countering? I mean, as your bands are openly discussing these issues.

I believe it’s always been routed in this scene. But when we started playing 6 years ago, it was taboo for me to be expressive on stage. I was an emotionally troubled 17 year old who didn’t find a place in the world and when I got to grab a microphone, I’d bash myself with it repeatedly and go into this state of euphoria where all my emotions were laid out there for the listener.

A lot of the bands at the time were weird about it, because it wasn’t manly. I could not care less about their preferred sense of masculinity back then, and still now. I’m just grateful that we get this platform to express this side of our brain that stays quiet during our normal lives.

But to me, that is what initially Une Misère, but maybe even more so Great Grief hit me so hard with: expression and vulnerability. Where a lot of the hardcore scene sticks to the tough guy image, where it’s all about being a hard man. It takes incredible guts to do that differently in my perception.

As much as I appreciate the era of NYHC and the stuff it has influenced. I’m just not the type of person to talk with their fists. Have Heart said it best: “Armed With A Mind”. That being said, I love moshing, hardcore dancing, all of it. It’s an integral part of the community. I wish more people would stage dive however.

Great Grief at Roadburn 2019, Photo: Justina Lukosiute

In that sense, perhaps you’re connecting more to that original strain of hardcore without the codes and cargo shorts?

Maybe, really I just see it as a free form of expression, where diversity should be celebrated, but there’s no place for oppressive behaviour.

Your show at Ladybird Skatepark to me was musically great, but you speaking about these issues was what really struck me (and clearly some other people). What did it take for you to stand up there and say this to a crowd of strangers? Because most hardcore shows feel like they challenge and confront the listener, where yours was embracing.

That gig was the one, the one where everything came together. It didn’t have to be the biggest crowd, and it didn’t have to be the nicest stage. We had the right people at the right time, and it left me incredibly thankful and full of love. This industry catches up to you, and for an anxious person like myself, I had an incredibly tough time with the first two shows because of it. When I go to shows, I’m not always in the best mindset, and sometimes I’m even trying to disappear.

For me to open up, it’s very natural now. But it took time to get to this place. I remember the first time I cried in front of an audience, I was called names. I felt weak. You can consider these shows and the banter between the songs a dialog between myself and I, as it seems to be universally accepted that at least person in a crowd of people might be having a rough time.

So to say that it is embracing is a good way to put it. I consider Great Grief a celebration of life. Even when I’m feeling like absolute death up there. And I want the crowd to feel the same.

How did this gig actually happen? Was it planned on beforehand? And did you as band pick the spot?

Walter offered us the slot, and we instantly said yes. It was an absolute no brainer. He picked the spot and we did it. It’s not the first time we play a skatepark, and it won’t be the last.

How was the process for you guys to end up at Roadburn in the first place? And particularly for you guys having played there before with Une Misère, what was that journey like?

This actually starts at the wonderful DIY fest Norðanpaunk in Iceland, last year. Walter saw Great Grief and said he loved it. We got offered to play and jumped at the chance since it is the best thing to come out of Europe since Speculoos spread.

I love that you mention Speculoos. It is the best, isn’t it?

The absolute greatest.

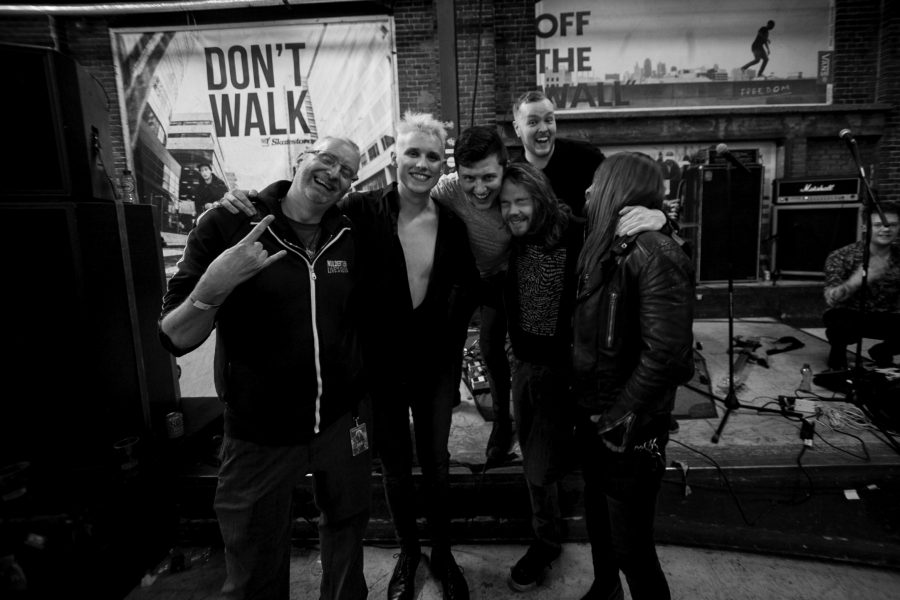

Great Grief with Walter Hoeijmakers, Photo: Justina Lukosiute

So how did you enjoy Roadburn itself as artist? What was the experience like in such an immersive festival where the boundary between artist and visitor is pretty much non-existent?

I love it. I find the relationship between the listener and the artist to be a very big part of how a band is perceived. Don’t get me wrong however, bands don’t need to be anyone’s best friend, but I do like it when I get to have a chat with someone I look up to.

The only negative listener experience I had at Roadburn this year was with the gentleman who kept spilling drinks on me and trying to untie my shoes as I was performing at the Green Room, I ended up slapping the drink out of his hand. Not my proudest moment. I hope he wasn’t too mad. Lex from Daughters said it best this weekend as I spoke to him backstage. “We’re all just a bunch of dicks, no one is better than anyone.”

I personally enjoy that you can have a chat with artists you like as a visitor. But there’s no entitlement so I’m already happy if I can stammer a thank you to an artist whose work matters to me.

I get that. I have had nice chats with some members of my favourite bands and it’s always an absolute thrill ride. Even when talking about the most mundane shit on earth.

Why do you perform wearing make-up and dressed up? And have you always done so in Great Grief?

I haven’t always done it. It was a part of me getting to know myself better in 2016. It’s how I feel most at home in my own skin. Think of it like a pair of sunglasses. Some people feel more comfortable among crowds as they wear sunglasses, as it leaves more to be seen. The same goes for me, my make-up and clothes leaves on a nice shade of confidence and appeal that no one can take away from me. I like to feel pretty – It’s me and my expression in its purest form.

Great Grief kicked off Roadburn 2019 at the Ignition on Wednesday, photo Maron Stills

Isn’t that in a way contrasting with the raw openness you display on stage?

I guess so. It’s also very simply a celebration of my queer identity.

And in that way perhaps also confrontational for some, as much as the openness is?

People may not be used to our kind of live show, and I can only hope that they are understanding and open minded.

So a lot of your performance is part of you as a person, as you said it’s also part of your queer identity. But how are you doing now? Has Great Grief helped you to find yourself?

If it wasn’t for me being in this band since I was 17 years old, I would be very lost. For a while this band sort of became my identity, which isn’t necessary positive. But suffice it to say, it has helped shape me into a better and kinder person.

I’m stressed out daily, being in two bands can be exhausting, but I’m incredibly grateful that I get to play music and have this platform to express myself. I really make sure not to take it for granted. I’m surrounded by amazing people, without them, I wouldn’t have much.

What future plans does Great Grief have at this point?

Create, play and prosper. Oh, and tour more.

To what dish (type of food) would you compare Great Grief, and why?

Oh, curry. A nice blend of spices, something sweet on the side, some brightly coloured peppers, and a brick of dense tofu in there, well marinated in flavour. Chickpeas? Some real layers of flavour. And spicy enough to make one shit their innards out.

Read all about Great Grief live at Ladybird Skatepark in: ‘The beauty in suffering: sounds that hurt & heal at Roadburn‘

Great Grief at Roadburn 2019, photo Maron Stills

Great Grief at Roadburn 2019, photo Maron Stills

Great Grief at Roadburn 2019, photo Maron Stills

Nog geen reacties!

Er zijn nog geen reacties geplaatst.